Alex Rose-Innes

When former President Barack Obama was in the White House, he ensured the rich history of pioneering women in STEM was shared with the world.

These women broke gender barriers and were leaders in building the early foundation of modern programming and unveiled the structure of DNA. They inspired environmental movements and their work led to the discovery of new genes.

It is now up to us to share their stories in order to inspire young women to pursue careers in STEM and change the world. Lest we forget their breakthrough histories, let us ensure it is written into history.

Ana Roqué de Duprey, paved the way for the Department of Education of Puerto Rico where she was born in 1853, by starting a school in her home at the age of 13. Her world was inhabited by books and she taught herself to read and write by age 3.

With a passion for astronomy and education, she founded several girls-only schools and the College of Mayagüez, which later became the Mayagüez Campus of the University of Puerto Rico. Roqué wrote Botany of the Antilles, the most comprehensive study of flora in the Caribbean at the beginning of the 20th century and was also instrumental in the fight for the Puerto Rican woman’s right to vote.

Lillian Gilbreth

Lillian Moller Gilbreth, an American psychologist and industrial engineer at the turn of the 20th century, was an expert in efficiency and organisational psychology, the principles of which she applied not only as a management consultant for major corporations, but also to her household of twelve children, as chronicled in the book and the film, Cheaper by the Dozen. Her long list of firsts includes first female commencement speaker at the University of California, first female engineering professor at Purdue,and first woman elected to the National Academy of Engineering.

Ruth Rogan Benerito

Ruth Rogan Benerito was an American chemist and pioneer in bio-products. She is credited with saving the cotton industry in post-WWII America through her discovery of a process to produce wrinkle-free, stain-free and flame-resistant cotton fabrics. Benerito also developed a method to harvest fats from seeds for use in intravenous feeding of medical patients. This system became the foundation for the system used today. After retiring, but still teaching university courses for eleven years more years, she received the Lemelson-MIT Lifetime Achievement Award both for her STEM contributions to the textile industry and her commitment to education.

Edith Clarke

Edith Clarke was a pioneering electrical engineer at the turn of the 20th century, known as a “computer” herself (someone who performed difficult mathematical calculations before modern-day computers and calculators were invented.) She struggled to find work as a female engineer but became the first professionally employed female electrical engineer in the United States in 1922. She paved the way for women in STEM and engineering and was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2015.

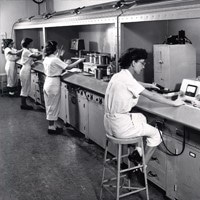

The Calutron Girls

Isolating enriched uranium was one of the most difficult aspects of the Manhattan Project, which produced the first nuclear bombs during World War II. Wartime labour shortages led the Tennessee Eastman Company to recruit young women, mostly recent high school graduates, to operate the calutrons using electromagnetic separation to isolate uranium. Despite being kept in the dark on the specifics of the project, the “Calutron Girls” proved to be highly adept at operating the instruments and optimising uranium production, achieving better rates for production than the male scientists they worked with.