Aarvin Jahajeeah and Jess Auerbach

For much of the pandemic, university spaces have sat empty and unused, while staff and students have scrambled to teach and to learn from home. As vaccination campaigns take off around the world, slowly the doors to lecture halls, laboratories and libraries are reopening. But these doors are leading to learning areas that have fundamentally changed.

Over the past 18 months, shifts that were already under way have swept through higher education in terms of how, where and with what resources learning and teaching take place.

Campuses will reopen with new tools in operation and new expectations from students, staff, and also communities. Here, we outline how universities could be rethinking their spatial use to adjust and to thrive in the new reality.

Learning hubs, not classrooms

Firstly, the idea of the lecture hall or classroom needs to be radically revisited. Lecture halls reflect the needs of training for the industrial century, when university prepared students to follow instructions, memorise information and repeat accepted formulae.

Lecture halls were deliberately designed to be uncomfortable (to prevent drowsiness in the face of drawn-out lectures), often cheap, and inflexible (to preserve the hierarchies of knowledge that no longer exist).

Today’s needs are radically different, and learning spaces must reflect this.

Rather than absorbing information from a focal ‘expert’, students need to be guided on how to parse multitudes of data and argument, and train themselves in rapidly shifting software, hardware and information environments.

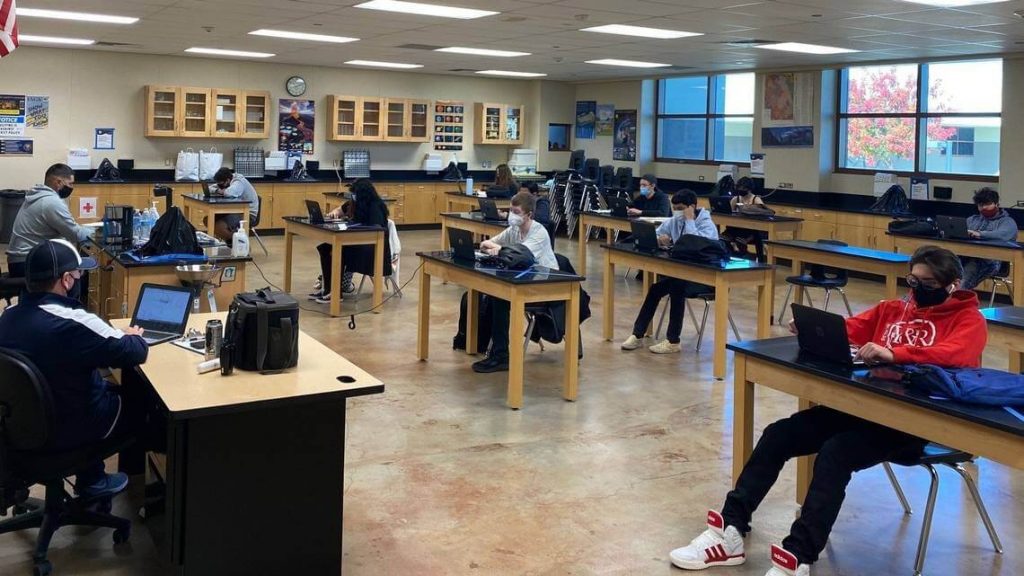

To support this process, learning spaces need to become equally flexible. They need to be multi-use, allow movement from large to small groups, be comfortable and pleasant to think in, and be able to incorporate emerging technologies for both students and staff.

These emerging technologies will simply become part of the fabric of an effective learning space and the technology will be sophisticated and invisible.

Learning spaces need to transition from ‘classrooms’ and ‘lecture theatres’ to learning hubs: like mainframes on computers, students need to be able to ‘plug in’ in whatever way is most appropriate to the task.

More and more, students will learn from project-based tasks that are responsive to the needs of society. Technology allows them to receive academic guidance while also immersing themselves in the complexity of the challenges they are being trained to overcome.

For example, engineering, architecture and social science students might all work on a low-cost housing initiative on site while continuing to receive instruction and support from university staff.

Fluidity between life and learning

Whereas, once the ‘classroom’ was imagined as the sole site of learning, we now appreciate that students can learn everywhere. This should be celebrated and designed for consciously, and with care.

Universities must adjust to accommodate the realistic needs of today’s students. They need to be operational 24 hours a day to enable students who have to earn income to also support themselves, and-or to fulfil care obligations at home.

University learning spaces need to enable continuity of learning during commute time or at unconventional hours. They need to create communities that bridge the online and offline worlds.

Relational responsibilities need to be a part of university services, as more and more students take career breaks to upskill at life stages where parenting responsibilities and care for elderly parents are often serious considerations.

Student accommodation should be flexible for shorter or longer periods of stay that allow students to access the resources of the broader university as and when needed, and still attend to other dimensions of their lives.

It should become a space where engagement and interaction is encouraged among students living on campus or elsewhere.

Each student on a campus needs to find ‘home’, community, and opportunities for growth.

Campuses of the future need to allow students to make a base, be it in a cubicle, a lab, or a bookable modular environment. Such spaces allow students to use the campus fully for its resources, both tangible and intangible, depending on their own unique needs.

One student may learn from home but come to campus for athletic facilities. Another may largely use the study spaces because their home environment is not conducive to learning. A third may attend in order to meet people, socialise, and network. All of these tasks are critical for academic success, wellness and the production of a functional society.

Spaces of uptime and downtime must, therefore, be designed into learning environments and should cater for different personality types. The analogy of one size fits all is redundant in modern teaching.

Rest rooms, in the literal sense of places where rest and contemplation is possible, must be created alongside high-energy spaces of gathering and conversation.

These spaces can be translated in the forms of nap pods, silent rooms, prayer rooms, breakaway spaces which can be either indoors or outdoors. Students will need to have the ability to make it their own.

Meeting local needs, answering global questions

Universities of the future will not be viable unless they meet local needs while answering global questions.

Each institution will need to be responsive and relevant to the particular learning ecosystems in which their students learn, and different scaffolding will need to be available in different places, depending on both gaps and opportunities.

In a knowledge environment, higher education will need to account for itself by demonstrating the use of its expertise to solve localised challenges.

Polluted river? Call in the environmental experts and have them solve the problem on the ground. Issue with supply and demand? Ask your local economist to work with the community.

Racial tension? Call in the social scientists and have them help build social bridges and move towards mutual understanding.

The above might sound idealistic to those who have tried to work with academics, but that is because many of us within the university system have forgotten the social contract that we think and write and teach as members of society.

Our skills – largely paid for by taxes – should be put to both theoretical and practical use. Paradoxically, geography will become less and less critical to successful learning, teaching and even the social responsibility described above.

Rather than experts being found on the university campus alone, the university will increasingly exist through the people it employs and the students it supports.

There is no reason that someone in Mongolia can’t give great support to kindergarten teacher training in the suburbs of South Africa if they happen to be the person with the most relevant expertise to do so.

These individuals will carry the brand, insight and impact of the institution with them wherever they need to be, and might set up pop-up ‘hubs’ all over the world that are networked and supported.

One will no longer have to go to the university closest to home, but rather the institution that can offer the best services to support individual needs. Today’s students were aware of this before the pandemic, and are now even more conscious of the choices that they have.

Institutions that insist on geographic presence will very likely lose the competitive edge in a changing teaching and learning environment.

Many of these changes – that are increasingly manifesting in the spatial organisation of learning – have long been in motion. The pandemic has simply accelerated and highlighted them.

Face-to-face relationships and learning are here to stay and have their merits, but they will inevitably be complemented by more flexible and responsive tools, technologies and spaces that will alter the learning environment.

Some universities have started to adapt their physical campuses to accommodate the new teaching and learning needs. The rest have to start planning for the post-pandemic world.

Aarvin Jahajeeah is an architect based in Cape Town. Jess Auerbach is a senior lecturer in anthropology at North-West University. This article first appeared in the University World News Africa Edition. The views expressed in the article are those of the writers and do not reflect views of Torque Media.